NOAH is a mapping application created by Disha Shetty, Maya Miller, Pankhuri Kumar and Ravie Lakshmanan, alumni of Columbia Journalism School, and Pietro Ceccato of SPACEBEL. It was made possible by a grant from the Brown Institute. This is a short report on NOAH’s development, and how can be used to uncover underreported stories on climate change.

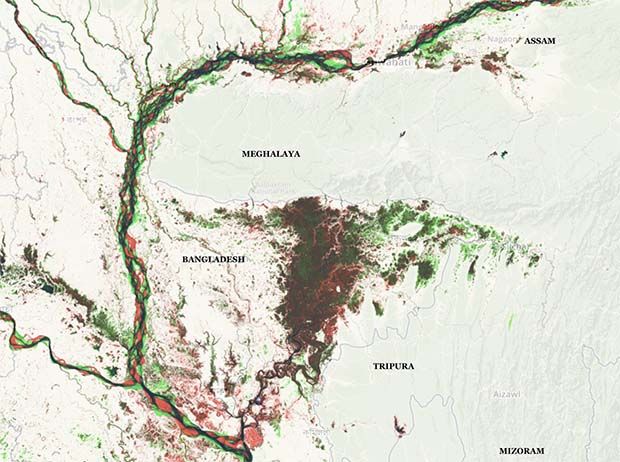

In Meghalaya, one of India’s greenest states, residents have noticed that some fruits now grow smaller, and that oranges are not as sweet as they once were. The state’s forests, once dense, have now visibly thinned out. With the help of the mapping application NOAH, reporting on this state revealed something more — that climate change in Meghalaya had consequences not just for India, but also for its southern neighbor, Bangladesh.

Meghalaya’s depleting forests has meant their sponge-like ability to absorb and retain water for a long duration has weakened, and so water runoff to flood-prone Bangladesh has increased. Satellite data confirm what ecologists explain in theory — when forests are depleted at rapid rates, the water security of surrounding communities is jeopardized.

Disha Shetty, an award-winning science journalist, used NOAH to uncover this story and incorporate its data and graphics into a report on the real-time impacts of climate change along this portion of the India-Bangladesh border — a report appearing this March in Indiaspend. With the backing of the Pulitzer Center, Shetty traveled to Meghalaya to speak to the people whose lives have been upended by the changes.

NOAH is a tool that houses the last four-decades of rainfall trends alongside the increases and decreases in bodies of water from across the planet. By combining these two datasets into a visual platform, its user can begin exploring how the prevalence of rain and the surface-water levels have shifted in communities.

Pietro Ceccato, a scientist and remote-sensing expert, first had the idea to combine the two datasets into one map in 2016. From having traveled the world on behalf of leading science centers in Europe and the U.S., as well as the United Nations, Ceccato saw first-hand how a dearth in data accessibility prevented decision-makers from being able to make well-informed choices. When the European Commission Joint Research Centre published a map on surface-water changes over time in Nature in 2016, he realized that adding rainfall data, which the International Research Institute tracked, onto this new map could provide the non-scientist a critical understanding of their environment.

When Shetty walked into Ceccato’s class on public health and climate change at Columbia University less than two years later, the two quickly realized their shared passion for data-driven work. Shetty, who was pursuing her master’s in science journalism at Columbia Journalism School, understood the potential for revelatory storytelling behind each spike in rainfall or dip in lake levels. She discussed making this application into a journalism resource with some of her then-classmates. They quickly formed team NOAH, and with support from the Brown Institute, they got to work.

NOAH aims to provide researchers with otherwise hard-to-access data, so that they can help shape the conversation as to where resources should be diverted. For journalists, NOAH is a place to find stories, and gather data to provide context for storytelling and a level of accuracy that is hard to achieve without the most complete picture possible. Ultimately, the team hopes the application enables people from across the world to have the information they need to learn more about their environment and water supplies, and to invite people to have a water frame-of-mind.