In December, the Brown Institute for Media Innovation convened a summit in New York with Hearst and OpenAI that brought together some of the most senior people in journalism and technology to wrestle with A.I. Editors and product leaders from the Associated Press, Bloomberg, ProPublica, the Washington Post, and Semafor sat alongside researchers from Stanford, Columbia, and partnership leads from OpenAI. The conversations were sophisticated and occasionally blunt. During our second panel on Deployed Systems, ProPublica’s Ben Werdmuller warned that journalism tends to treat technology as something that happens to it, like an asteroid.

Two months later, during midwinter recess in February, we took the same set of questions, how A.I. works, what it can do for a reporter, what your newsroom’s policy should be, to a very different room: a group of high school student journalists from across New York City’s five boroughs, gathered for the Youth Journalism Coalition’s Journalism for All program to launch newsrooms at their schools. Students ranged from sophomores to seniors, and most of them had never reported a story.

The conversations that followed taught us something that a room full of industry leaders had not.

The students hadn’t arrived empty-handed. CJ Sánchez, the director of New York City’s Youth Journalism Coalition, had structured the Journalism for All program so that each school team came to the intensive with data from a community survey they’d already conducted to map the information needs of their school. The survey surfaced everything from the languages their communities want news in, the platforms and formats they prefer, and, most pointedly, the gaps. “A lot of them found that students don’t know what they need to graduate,” Sánchez said: basic things like graduation requirements, internship opportunities, college guidance. The parallel to civic journalism is hard to miss: these are the same kinds of essential, hyperlocal facts that small local outlets used to be the go-to for. Where do you vote? What’s on the ballot? What do you need to graduate? The students were already doing the work of identifying unmet information needs in their communities before we ever introduced A.I.

We structured the week around the same arc that had organized the December summit. Day one was about use. We started with what the students already knew, then threw them into reporting. The Trump administration had just released new Dietary Guidelines complete with a revamped food pyramid, a national story that lands directly in a school cafeteria. We gave the students NYC lunch menu data, nutrition reports, and school kitchen dashboards, and asked them to use A.I. to find story angles. Some found genuine leads. Others got confidently wrong answers, fabricated nutritional comparisons, and hallucinated statistics. Which was the point. At the summit, the AP’s Troy Thibodeaux had said that LLMs can be wrong, but sometimes they’re wrong in interesting ways. The students discovered this for themselves.

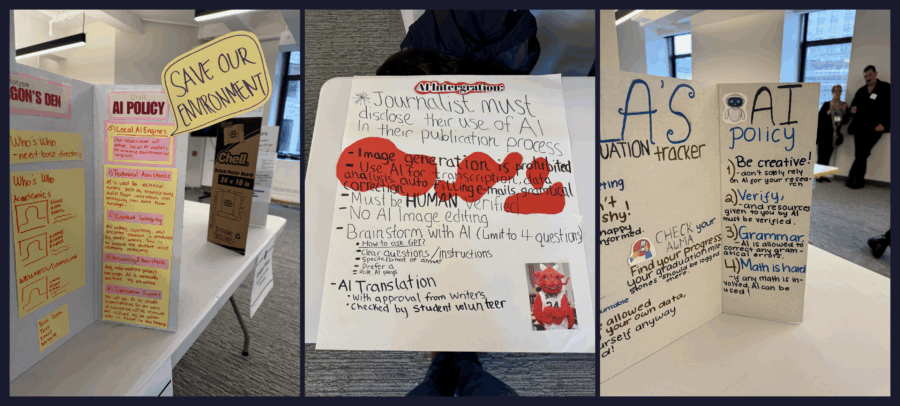

Day two went under the hood, from language models, token prediction, bias, and the difference between alignment and capability. On day three, students drafted A.I. usage policies for their school newsrooms using the Poynter framework and a simplified framework produced by the Thomson Reuters Institute. Each school’s team worked from their own community’s data, teasing through the concerns their surveys had surfaced and building tools specific and local by design. A recurring theme at the December summit had been that A.I. innovation has to be bottom-up: one town, one meeting, one small GPT that does one part of one job. In the high school sessions, this happened naturally.

The Brown Institute occupies an unusual position: we work with students and professionals at every stage of the pipeline, and that vantage point is what makes the pattern visible. The conversation about A.I. is not one conversation. It’s several, running in parallel, and they only sometimes overlap.

The graduate students at the Columbia Journalism School approach A.I. with practical curiosity. They attend our A.I. Club to hear practitioners like Clare Farley at Reuters, who used A.I. to transcribe thousands of handwritten prison temperature logs, surfacing patterns of dangerous heat that would have been nearly impossible to document otherwise. For them, A.I. is a professional instrument to master. The undergraduates at Columbia and Barnard lean skeptical. In a computer science course I teach called Writing with/and Computing, they examine technology through a critical humanistic lens, interrogating errors, surveillance, the question of who benefits. Their wariness is productive, the kind that keeps a society honest about what it’s building.

The professionals have moved past all of this. At the December summit, the conversation was operational: workflow integration, editorial guardrails, the race between deployment and evaluation. Nobody debated whether to use A.I. They debated how fast. Gina Chua of Semafor was vibe-coding newsroom tools for a staff of thirty. The AP was building podcast-monitoring systems for its democracy team. The question was not if but how much.

And then there are the high school students.

We expected them to be the most enthusiastic adopters. They use ChatGPT for homework help, for structuring essays. They are not intimidated by technology.

But their dominant concern was not accuracy, or bias, or jobs.

It was climate.

Again and again, across sessions and across schools, they wanted to know about the energy consumed by data centers, the water used for cooling, the carbon footprint of training and use. This was not a talking point. It was a pervasive anxiety. When we demonstrated something powerful, the first response was often not “how does this work?” but “what does this cost the planet?”

Sánchez told me afterward that the students’ reaction was “way more guarded than I expected.” But they weren’t disappointed. They were pleased. The students’ environmental concern, they said, “speaks to their curiosity and understanding of their impact in the community around them. I think it’s not a coincidence that we have a room full of burgeoning journalists” and this is on their minds. The instinct to ask what costs are hidden beneath a convenient surface. That’s a journalistic instinct. It’s what brought them to the program in the first place. At the same time, Sánchez was clear-eyed about the stakes of not teaching these tools. These are students at schools that are underserved, they said, “where they are not getting rich access to cutting-edge technology or an understanding really of what the job market’s gonna look like in ten, fifteen years.” AI literacy, for this population, isn’t optional enrichment. It’s an equity issue.

At the summit in December, the environmental cost of A.I. wasn’t mentioned. Dozens of senior journalists and technologists spent an entire day discussing partnerships, deployment, model behavior, traffic, and the future of the information ecosystem, and nobody mentioned energy or water. This is not because those people don’t care about climate. It’s because when you’re deep in the operational questions, from how to evaluate outputs to how to avoid replicating the mistakes of social media, the resource cost of the infrastructure recedes into background assumption.

The sixteen-year-olds have not made peace with it. They weren’t sure they should.

I don’t think they’re wrong. There is a version of the A.I. conversation that treats environmental costs as a footnote, something to acknowledge before getting to the exciting part. Most professional discussions work this way. The high schoolers rejected that framing. For them, the question of whether a tool is worth using is inseparable from the question of what it takes to run. It’s not naive. That’s a more complete accounting.

This is one reason the Brown Institute has invested in teaching students and newsrooms to work with small, local language models. These are open-source systems that can run on a single machine, without sending data to a third-party server and without drawing on the enormous computational infrastructure that powers the frontier models. Small local models are not as capable as GPT or Claude for every task. But they address several of the concerns that converged in that room at once: they consume a fraction of the energy, they keep sensitive reporting materials off the cloud, and they give a newsroom sovereignty over its own tools, free from dependency on a company whose incentives may not permanently align with yours.

At the December summit, Werdmuller had described using local models for exactly this reason: when the risk of a subpoena means source material physically cannot live on someone else’s server. For the high schoolers, the appeal was broader. A model you run yourself is a model whose costs you can see. It makes the resource question concrete rather than abstract, which is exactly what they were asking for.

The policies these students drafted on the last day grappled with the same tradeoffs the summit panelists discussed: the efficiency of automated transcription versus the privacy risk of uploading audio to third-party servers, the speed of A.I.-assisted data analysis versus the irreplaceable value of a reporter who knows their community. But they also asked questions that few professional newsroom policies think to include: Is this use proportionate? Is the output worth the input, not just editorially, but ecologically?

Sisi Wei of CalMatters and the Markup closed the December summit by calling for what she termed radical collaboration: a willingness to stop building the same tools in parallel and start sharing engineering resources across newsrooms. I’d add a corollary: radical listening. The youngest people entering journalism are bringing moral questions that the profession has been too operational to ask. We should stop treating that as a gap in their understanding and start treating it as a correction to ours.